What do you first think of when the talk of ancient civilization comes up? Depending on where you are from and how you are brought up, different pictures might pop up in your head. But a common picture that helps a lot of us relate to ancient civilizations in general, is the rather simple form of Greek architecture temples with thick columns on the bottom and a triangle gable pediment at the top that confines a sculptured scene of a fight or a godly feast.

But what is the secret to ancient Greek architecture that makes it so timeless and widely accepted throughout history?

Over two thousand years have passed since the famous Greek architecture’s end and scores of short-lived or long-lasting styles have come and gone. But what humans have rebounded to over and over, is the ancient Greek architecture with its strong and peaceful forms.

Harmony, balance, and symmetry rule the proportions, forms, and geometry of almost all Greek architecture characteristics; general rules that have reached such perfection here that their intricate simplicity has made them timeless the way they’ve proven through all this time.

Before getting to details and separate styles of the Greek architecture, let us talk about tenets that are shared throughout almost 800 years of architectural evolution in the mainland Greece and its neighboring territories, islands, and peninsulas from sometime around 900 B.C. to the first century before the Birth of Christ.

Almost all major Greek architecture projects have been designed and coordinated by a single architect in charge.

Meaning these buildings were not merely an intuitive collaboration of native communities or only the result of their vernacular effort.

But they reflect an established civilization where diverse groups of professionals would be directed by an architect to express a unified state of the art building; whether it was a temple, an open theatre, a Stoa or a public market, or a Bouleuterion where city councils would convene.

For instance, in case of Greek architecture temples, first, the architect would come up with the style, proportions, detailed dimensions of columns, the entablature that would mount on them, and finally the pediment with gables at both ends on top.

He would also have to design the inner chamber (or the Naos) where the statue of their gods and the gift they presented them were stored. Much of the parts in ancient Greek architecture temple we are talking about, like the pediment on top, or the immediate beam over the columns (or the Entablature) include sculpted scenes and paintings.

So, sculptors were also gathered both from mainland Greece and abroad to have their part too.

So first of all, stonemasons had to chisel stone boulders that were usually brought in locally, into swiss-precision blocks that would fit together.

Then these Lego pieces had to be put onto one another. So, workmen had to be employed to put up the scaffoldings and lift up and mount the stone blocks on top of each other.

The stones were so fit that there was no need for mortar to hold them together. Instead, one of the most famous Greek architecture characteristics is the metal hooks or clamps they used to brace columns against earthquakes. So, metalworkers had to be invited too.

Finally, as we said earlier, all the stonework had to be spiced up by ornamental paintings. So, painters would make the final touch on various Greek architecture elements as a wrap up.

All these different types of artisans and artists had to be orchestrated to cooperate toward making a strong statement in ancient Greek architecture work of art. A collaborative feat that wasn’t possible without an architect as the central party.

Now that we have a rough image of how a famous Greek architecture was erected, we can get deeper on different styles that were practiced in ancient Greek architecture.

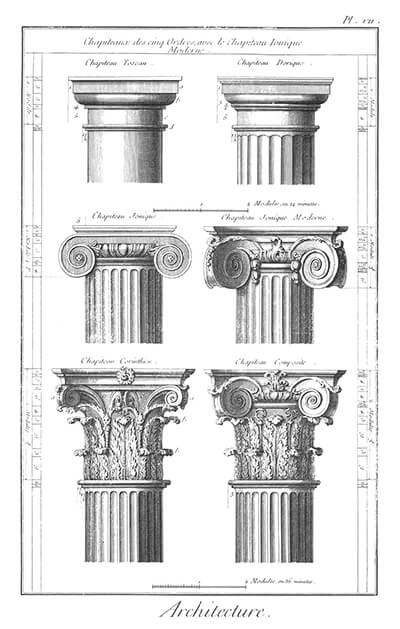

The most distinctive feature that separates Greek architecture styles is reflected in the types of columns they would use. Greeks can’t be counted as big fans of drastic changes on this account, because the overall forms they used in their columns have been preserved through almost eight centuries of Greek architecture prime.

Starting from the oldest to the latest, there were three distinct styles that were called Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

Some features though, run the same across these column orders. They all were fashioned with grooves down their sides. These rippling flutings would give a sense of depth and extra contrast to the building.

Columns in the Doric order are the simplest. They were the thickest among the three types. Doric columns don’t have any extra base on the bottom and they were capped by a single square capital stone at the top.

They were tapered. So, a Doric column was narrower at both ends than in the middle; with the upper end slenderer than the bottom.

The beam over the columns (also called the entablature or frieze) in the Doric order, was way thicker than the other two styles that succeeded it. The span between two thick Doric columns was shorter due to the period’s primary structural standards.

Ionic order of the Greek architecture, on the other hand, had thinner columns, two scrolls at either side of the top capital, and would finish with a base stone on the bottom.

Corinthian was fanciest among the three and came last in time. It was later vastly used by the Romans. The upper part of a Corinthian column was decorated with acanthus leaves and scrolls which gave an identical look from every angle.

Corinthian order had the leanest and tallest columns among the three types and supported wider spans in between.

It should be mentioned here that Greek architecture’s Doric order was mostly practiced on the Greece mainland and other central Aegean territories. While Ionic order was more common in Greek islands and the Corinthian order was more widely used in the Hellenistic and Roman era.

So far, it might have looked like we were only talking about temples, but Greek architecture is way more than that.

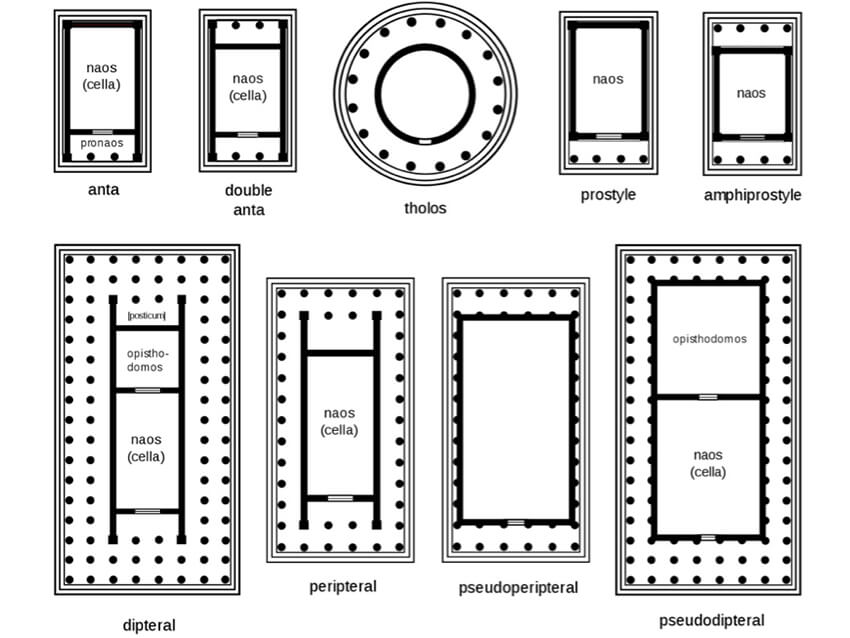

Although there are various types of temples with different ground plans as you can see below, other public and private establishments were genuinely first developed by the Greeks.

Stoa was a colonnade that surrounded the public market or Agora. They were the place for peddlers or other seasonal merchants to sell their items. Almost all major cities of the ancient Greek architecture had Stoas as an important public arena in their municipality area.

Open theatres were another urban hotspot that were first defined and coined by Greeks. They were circular open arenas with sloping sitting spaces that overlooked a central circle where the Orchestra would perform and a stage where the dramatic theatrical performances were played.

Greek theatres would usually use sloping hillsides that overlooked the city below or a gripping natural vista to their benefit. So, the scene behind the stage would play as the background for the performance.

Greek architecture portrays other characteristics of the people who built it. They were “literally and spatially democratic”. Now the word “Democratic” means way more than it did back then.

But city councils were various affairs of the citizens were discussed and settled were yet another famous Greek architecture form they developed for the first time.

Bouleuterions were rectangular roofed chambers with stepped seating areas all around and a central floor where the speaker would address the opposing parties with an altar behind him. Sound familiar? You must be thinking about the British Parliament and its famous House of Commons chamber in Westminster.

Now you know they have borrowed the ancient Greek architecture characteristics of Bouleuterions.

Examples can go on and on but for brevity, we will only get to three of the most defining Greek architecture monuments here. Let’s take a look.

Parthenon in Acropolis, Athens

Parthenon’s bright marble has withstood centuries of time and human ravage and they still stand out as the most eye-catching element across Athens.

The temple’s rectangular plan is surrounded by Doric columns and square capitals at their top. The whole temple stands on a three-stepped platform.

17 columns on each of the northern and southern fronts and the 8 columns at either of the east and west façades frame two walled chambers inside called Cella.

The main columned part of Parthenon’s Greek architecture is topped by a relatively slim horizontal beam; consisting of a plain layer right on top of the square capitals over the Doric columns and then an alternating band of vertical grooves (Triglyphs) and ornamental sculptures (Metopes).

The final upper part of the Parthenon architecture is a slow triangle called Pediment that’s visible on the eastern and western fronts. It contains sculptural work that each depict a story of some sort; a fight between the divine and evil or a godly occurrence like the birth of Athena on the east side.

Of the three Doric, Ionic, and Hellenistic styles over the course of famous Greek architecture, Parthenon is the climax of the Doric era.

Parthenon might seem straight from every angle, but the truth is, you almost can’t find any straight lines across the temple. This Greek architecture masterpiece is where imperfection is perfectly made and all for a reason.

Endorsed by the Roman author, Vitruvius, the architects have deliberately made some unusual refinements to defy the optical illusions of the human eye.

For example, outer columns at the corners are thicker than the rest to tackle the illusion caused by the background sky at the temple’s edges.

Such perfect care to adjust to the imperfections of human eye comes from Greek architecture’s deep understanding of nature.

The Great Theatre of Epidaurus in Epidaurus

Theatres were not only a place for drama and visual performance. They were also linked to the sacred body of priests. That’s why a lot of Greek architecture theatres were close to religious sanctuaries and attracted visitors from all around to “heal” by watching dramatic performances.

The strong and eye-catching geometry of Epidaurus Greek architecture is not just a sight for the eye, but it was and still is a treat to the ears too. It creates a fascinating acoustic experience for all the spectators even in the furthest back rows.

The stepped form of the encircling seating area that houses up to 14000 viewers traps voices of performers at the center and filters out noises in between.

The Great Theatre of Epidaurus represents a strong example of ancient Greek architecture and its effect is apparent on various Modern Greek architecture buildings like the country’s parliament chamber.

Stoa of Attalos, Agora in Athens

With Acropolis at the background, the Stoa of Attalos in Athens shows the magnificence of ancient Greek architecture through its unified rows of Doric and Ionic columns.

Over on the east side of the Agora Square, this two-story Stoa still stands and conjures the vibrant and lively urban life of Athenians in distant years.

The deliberate use of famous Greek architecture elements and proportions are present here, just as it rules in other ancient buildings of the capital.

What other monumental temples, theatres, or any other urban buildings strike you as inspirational as the ones we talked about here? Tell us about it first hand in the comments section below.

Comments