What is the ancient Mesopotamian architecture you ask? or what are the characteristics of the Mesopotamian architecture?

It is way too soon to ask these questions, believe me! Let’s get off to a better start; just hear me out:

Have you ever wondered why there are seven days in a week?

Or why they are called Saturday, Sunday, Monday, and so on? Let’s connect the dots.

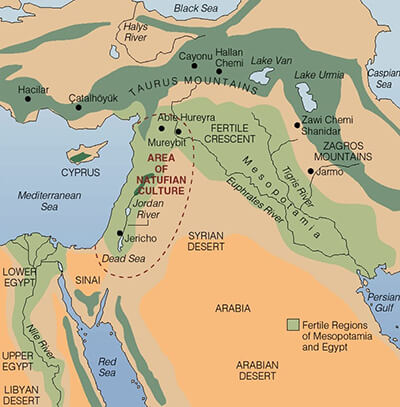

Thousands of years ago, in an area that we call the Middle East today and on a piece of land we call Iraq now, life existed between two old rivers that still run to this day.

Tigris and Euphrates surface from the same mountain in modern-day Turkey; then each takes a thousand-mile-long journey across a vast plain land of dry soil with palm trees here and, there but empty of any mountain, and finally reunite on where the Iran-Kuwait border lies today and shed into the Persian Gulf.

Now we know that this land, also known as the cradle of civilization, has been the scene to a game of thrones and kingdoms for thousands of years. A procession of kings and Empires way longer than any George R. R. Martin could ever write about in several lifetimes.

The most powerful dynasties over these long millennia with the greatest Mesopotamian architecture were Sumerians, Assyrians, and Babylonians.

There’s no chronological order to the rule of each Empire through. The history of Mesopotamian architecture is way more complicated than that, so these civilizations might have overlapped.

But suffice it to say that Sumerians roughly came earlier than the other two and Assyrians were straddled by the early and late Babylonians.

Much of the Mesopotamian architecture and culture can be compared to their counterparts in Egypt that are probably better known through their stone pyramids; but it’s ironic to know that Mesopotamian Empires, all the way up from the early Sumerians and onto their successors, had bustling cities and booming trade relations with their neighboring powers like the Greek and the Egyptian.

But what gives away the existence of these historic vibrant civilizations?

Through the vast flatlands between the two rivers, you bump into occasional mounds of rubble. But if you excavate you’ll find that it is not geography that’s making a joke here. These are remains of great ancient Mesopotamian architecture of cities and citadels.

Gigantic forts and temples made of mud and clay bricks that have been wasting away over the ast few thousand years, since their glory.

This glory is written on cuneiform clay tablets (as opposed to the Egyptian Hieroglyphs on papyrus) and it explains their trade and business dealings.

Sometimes on baked-clay plates and sometimes on glazed tiles, they portray kings accepting presents or kneeling captives or even scenes of their valor in battle; all of which are the theme of the buildings we’ll get into shortly.

Even the first law book was written by the Babylonian King, Hammurabi; although its nothing like the fancy human rights we have today, but still, it’s good to know where the fountain has run.

OK, it’s time to get back to our “why-weeks-are-seven-days-and-with-such-names” story after this rather long segue into the glory of kings between rivers.

All ancient civilizations, Mesopotamians included, were more watchful of the sky above than us, who are caged with overshadowing skyscrapers and meager streets in modern cities.

They imagined the earth as a flat surface that is cupped in a revolving sphere. This sphere with all its sparkling stars was called the “vault of heaven”.

But since they were smart people, they had realized that the stars were still in the sky and so they’d given names to familiar shapes these stars would make. Names like Great Bear; just like us with the constellations today.

But some of the stars, or at least what they thought to be stars, were not as bogged down like the others. They seemed free to roam around the sky vault, unlike the rest that would reappear every night at the same spot.

That was why Mesopotamians assumed mighty powers for each one of these handful roaming stars. Moon and Sun as the most obvious, along with Saturn and the other four planets known to them back then, each would bring a joyous or terrifying message.

For example, Mars was the sign of War or Venus would speak of love.

The seven made up the days of what they called a week with each day representing one of the revered stars. Saturday for Saturn, Sunday for the Sun, Monday for the Moon, and the rest with names that are unknown to us today; but the French and Italian still call their weekdays just like how the Mesopotamians did. Who would’ve thought Mesopotamia was this close to us?

If you liked this little ancient saga, you can find a tone more in a great book that is kind of like “history for people in a hurry” by E. H. Ernst Gombrich.

Now; with this insightful background about Sumerians, Assyrians, and Babylonians, examining the ancient Mesopotamian architecture just got a lot easier.

Here, we are going to bring you examples from different historical periods between the two rivers and their most notable remnants to find out “what are the characteristics of the Mesopotamian architecture”.

We are going to get to each archeological site or relic on an oldest-to-the-most-recent basis from sometime around 3000 BC.

Starting from the religious temples of Sumerians, moving forward to the Early Babylonians and their palaces where the first human right manifest was engraved on stone, and finally to the Assyrians and Late Babylonians’ remarkable architectural feats.

So, let’s get to it.

Ur Ziggurat

We mentioned how in the ancient Mesopotamian architecture, some of the stars in the sky were revered as mighty powers and people saw them as a way to predict the future and their fortunes.

Well, the masses’ belief would take them to these gigantic buildings, usually in shapes of stepped pyramids, with a temple on the upper-most platform at the top and terraces on lower levels with a serpentine route with staircases leading to the temple.

By presenting valuable gifts, people could hear priests foresee their doom or salvation based on what the gods in the sky would tell them.

Ur Ziggurat or other Ziggurats we’ll get to further along, are all assembled around the same geometry and philosophy.

Belonging to 2125 B.C., this particular Ziggurat of Ur is made of brick and mortar walls to hold the mass of condensed soil inside; all making up the stepped pyramid that can be approached by three converging mild staircases at one side.

Royal Tomb of Ur

Sir Leonard Woolley was the first to discover and excavate the huge burial site now known as the Royal Tombs of Ur.

More than its remarkable underground Mesopotamian architecture, it gives an exceptional insight into the afterlife beliefs of the Sumerian.

It contains more than 2500 ordinary and 16 special burial sites that appear to belong to exceptionally wealthy individuals; most likely members of a royal family buried with golden sheath and dagger and additional copper weapons and a set of toilet instruments.

All the relics found at the Royal Tombs of Ur reflect people’s connection with their afterlife fate.

Tchoga-Zanbil Ziggurat of Elam

The biggest Ziggurat in the world sits in modern-day south-west Iran, 19 miles away from the ancient site of Haft Tepe.

The same philosophy that shaped the Ur Ziggurat prevails here. Although it is technically outside the bound of the twin rivers, it follows the same Mesopotamian architecture principles.

Chogha Zanbil was built around 1250 B.C. and was ravaged by an Assyrian King in 640 B.C.

Over the course of its 3000-year history, Choha Zanbil has sustained three stories of its original five levels. It was also crowned with a temple at the top; all the same as other ziggurats in the Mesopotamian architecture.

Lamassu of Assyria

Lamassu is more of an element within Mesopotamian architecture.

It used to represent an Assyrian deity with protective powers that had a human head with rippled-beard and was donned by an ancient helmet, the body of an ox, a bull, or a lion, and wings of a bird.

These Assyrian elements were widely used across both Mesopotamian architecture and other civilizations in the Middle East.

They were later at the entrances of Persepolis, used as artifacts by the great Achaemenid Empire of Persia.

Ishtar Gate

Roughly after Assyrians in time, King Nebuchadnezzar II of Neo-Babylonians restored their ancestors’ glory by recapturing most of the Mesopotamian soil. He was also the Babylonian king who captured Jerusalem.

He was the one who ordered the construction of a new gate for the city of Babylon in honor of the goddess Ishtar. It featured glazed bricks in black and blue at the background and gold portrays of lions, dragons, bulls, aurochs, flowers, and Assyrian Lamassus over the glazed bricks.

Tower of Babel

There is no solid historical or archeological evidence to prove that the Tower of Babel really ever existed on this earth; only an excerpt from Herodotus, the Greek historian in the 5th century B.C.

He says “In the topmost tower there is a great temple, and in the temple is a great bed richly appointed, and beside it a golden table. No idol stands there. No one spends the night there save a woman of that country, designated by the god himself, so I was told by the Chaldeans, who are priests of that divinity”.

Mythical depictions of the Tower next to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon are as close as you can get to these wonders of the ancient world; all of which could be merely a figment of the imagination.

It’s worth mentioning that the Seat of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France is believed to have been an adaptation of the tower of Babylon and its symbol of the man’s defiance against the gods.

Conclusion

Mesopotamian architecture and its kings between the two rivers have been gathering dust for quite a while now, but believe it or not, we are sitting upon their seemingly-primary discoveries and genius inventions.

Writing, Astronomy, Law, Urban Planning, and of course the Mesopotamian architecture are the fruits of this rich succession of civilizations that once grow and fell on the fertile “land between the rivers”.

What else can be added to this list of notable buildings we gathered of the Mesopotamian architecture?

Help us tailor the best examples out of the whole bunch of sites discovered in Mesopotamia by leaving a suggestion in the comments section below.

Comments